Man of Constant Sorrow O Brother Where Art Thou

| "Man of Constant Sorrow" | |

|---|---|

| Song by Dick Burnett | |

| Published | 1913 |

| Recorded | 1927 (unreleased) |

| Genre | Folk |

| Label | Columbia |

| Songwriter(s) | Traditional |

"Man of Constant Sorrow" (likewise known as "I Am a Man of Constant Sorrow") is a traditional American folk vocal outset published by Dick Burnett, a partially blind fiddler from Kentucky. The song was originally titled "Farewell Vocal" in a songbook by Burnett dated to effectually 1913. A version recorded by Emry Arthur in 1928 gave the vocal its current titles.

There are several versions of the vocal that differ in their lyrics and melodies. The song was popularized by The Stanley Brothers, who recorded the song in the 1950s; many other singers recorded versions in the 1960s, near notably by Bob Dylan. Variations of the song have also been recorded under the titles of "Daughter of Constant Sorrow" by Joan Baez, "Maid of Constant Sorrow" past Judy Collins, and "Sorrow" by Peter, Paul and Mary. Information technology was released equally a single by Ginger Baker's Air Forcefulness with vocals by Denny Laine.

Public interest in the song was renewed later the release of the 2000 film O Blood brother, Where Fine art One thousand?, where it plays a cardinal office in the plot, earning the iii runaway protagonists public recognition as the Soggy Bottom Boys. The song, with lead song past Dan Tyminski, was featured on the film's highly successful, multiple-platinum-selling soundtrack. That recording won a Grammy for Best Land Collaboration at the 44th Annual Grammy Awards in 2002.[1]

Origin [edit]

The vocal was beginning published in 1913 with the championship "Farewell Song" in a six-song songbook past Dick Burnett, titled Songs Sung by R. D. Burnett—The Blind Human—Monticello, Kentucky.[2] There exists some incertitude equally to whether Dick Burnett is the original writer. In an interview he gave toward the end of his life, he was asked about the song:

Charles Wolfe: "What almost this "Farewell Song" – 'I am a man of constant sorrow' – did you lot write it?" Richard Burnett: "No, I remember I got the ballad from somebody – I dunno. It may be my song ..."[3]

Whether or not Burnett was the original author, his piece of work on the song tin can be dated to about 1913. The lyrics from the 2nd verse—'Oh, six long twelvemonth I've been bullheaded, friends'—would concur truthful with the year he was blinded, 1907. Burnett may take tailored an already existing vocal to fit his blindness, and some claimed that he derived it from "The White Rose" and "Downwardly in the Tennessee Valley" circa 1907.[4] Burnett too said he idea he based the melody on an old Baptist hymn he remembered as "Wandering Male child".[2] Even so, according to hymnologist John Garst, no song with this or a similar title had a melody that can be identified with "Constant Sorrow".[5] Garst nevertheless noted that parts of the lyrics suggest a possible antecedent hymn, and that the term 'man of sorrows' is religious in nature and appears in Isaiah 53:iii.[5] [6] The song has some similarities to the hymn "Poor Pilgrim," also known as "I Am a Poor Pilgrim of Sorrow," which George Pullen Jackson speculated to take been derived from a folk song of English origin titled "The Green Mossy Banks of the Lea."[vii]

Emry Arthur, a friend of Burnett, released a recording of the song in 1928, and also claimed to have written it.[5] Arthur titled his recording "I Am a Man of Constant Sorrow", the name that the vocal came to be more popularly known. The lyrics of Burnett and Arthur are very similar with modest variations. Although Burnett's version was recorded earlier in 1927, Columbia Records failed to release Burnett's recording;[2] Arthur'due south single was thus the primeval recording of the song to be released, and the tune and lyrics of Arthur'south version became the source from which most later versions were ultimately derived.[5]

A number of like songs were found in Kentucky and Virginia in the early 20th century. English folk song collector Cecil Sharp collected iv versions of the song in 1917–1918 as "In Old Virginny", which were published in 1932 in English language Folk Songs from the Southern Appalachians.[2] The lyrics were different in details from Burnett's but similar in tone. In a version from 1918 by Mrs Frances Richards, who probably learned it from her father, the first poetry is nearly identical to Burnett's & Arthur'due south lyrics, with small-scale changes like Virginia substituting for Kentucky.[iv] [8] The vocal is thought to be related to several songs such as "East Virginia Dejection".[8] Norman Lee Vass of Virginia claimed his brother Mat wrote the song in the 1890s, and the Virginia versions of the song show some relationship to Vass's version, even though his melody and most of his verses are unique. It is thought that this variant was influenced past "Come up All You Fair and Tender Ladies"/"The Picayune Sparrow".[4] [5]

An older version described by Almeda Riddle was dated to around 1850, just with texts that differ substantially after the first line.[5] John Garst traced elements of the song back to the hymns of the early 1800s, suggesting similarity in its melody to "Tender-Hearted Christians" and "Judgment Hymn", and similarity in its lyrics to "Christ Suffering", which included the lines "He was a human of constant sorrow / He went a mourner all his days."[9]

On October xiii, 2009, on the Diane Rehm Evidence, Ralph Stanley of the Stanley Brothers, whose autobiography is titled Man of Abiding Sorrow,[ten] discussed the song, its origin, and his attempt to revive it:[11]

"Man of Constant Sorrow" is probably two or 3 hundred years erstwhile. But the get-go fourth dimension I heard it when I was y'know, like a pocket-sized boy, my daddy – my begetter – he had some of the words to it, and I heard him sing information technology, and we – my brother and me – we put a few more words to it, and brought it dorsum in being. I guess if it hadn't been for that it'd have been gone forever. I'm proud to exist the one that brought that song back, because I think it's wonderful.

Lyrical variations [edit]

Many subsequently singers have put new and varied lyrics to the song. Well-nigh versions have the vocaliser riding a train fleeing problem, regretting not seeing his old dear, and contemplating his future death, with the hope that he will meet his friends or lover again on the cute or gilded shore.[4] Most variants offset with similar lines in the outset verse equally the 1913 Burnett's version, some with variations such every bit gender and home state, along with some other small-scale changes:[12]

I am a human of constant sorrow,

I've seen trouble all of my days;

I'll bid farewell to old Kentucky,

The place where I was built-in and raised.

The 1928 recording past Emry Arthur is largely consistent with Burnett'south lyrics, with only pocket-sized differences.[12] However, the reference to incomprehension in the second verse of Burnett's lyrics, "vi long twelvemonth I've been bullheaded", had been changed to "half-dozen long years I've been in problem", a change as well plant in other later versions that comprise the verse.[13]

In around 1936, Sarah Ogan Gunning rewrote the traditional "Man" into a more personal "Girl". Gunning remembered the tune from a 78-rpm hillbilly record (Emry Arthur, 1928) she had heard some years earlier in the mountains, just the lyrics she wrote were considerably different from the original later the first poetry.[12] [14] The modify of gender is as well plant in Joan Baez'southward "Girl of Constant Sorrow" and another variant of the song like to Baez's, Judy Collins'due south title song from her anthology A Maid of Abiding Sorrow.[15]

In 1950, The Stanley Brothers recorded a version of the song they had learnt from their father.[13] [xv] The Stanley Brothers' version contains some modifications to the lyrics, with an entire poetry of Burnett'south version removed, the last line is also different and 'parents' of the 2nd verse take turned into 'friends.'[12] The performances of the song by the Stanley Brothers and Mike Seeger contributed to the song's popularity in the urban folksong circles during the American folk music revival of the 50s and 60s.[14]

Bob Dylan recorded his version in 1961, which is a rewrite based on versions performed by other folk singers such as Joan Baez and Mike Seeger.[16] [17] A verse from the Stanleys' version was removed, and other verses were significantly rearranged and rewritten. Dylan as well added personal elements, changing 'friends' to 'mother' in the line 'Your mother says that I'm a stranger' in reference to his then girlfriend Suze Rotolo'due south mother.[18] In Dylan's version, Kentucky was changed to Colorado;[thirteen] this change of the state of origin is mutual,[iv] for example, Kentucky is changed to California in "Girl of Constant Sorrow" by Joan Baez and "Maid of Constant Sorrow" by Judy Collins.

Bated from the lyrics, there are too meaning variations in the melody of the song in many of these versions.[fifteen]

Recordings and encompass versions [edit]

| "I Am a Human being of Constant Sorrow" | |

|---|---|

| Song past Emry Arthur | |

| Released | January 18, 1928 (1928-01-18) |

| Genre | Erstwhile-fourth dimension |

| Length | 3:xviii |

| Label | Vocalion |

| Songwriter(s) | Unknown |

Burnett recorded the song in 1927 with Columbia; this version was unreleased and the main recording destroyed.[2] The first commercially released record was by Emry Arthur, on Jan 18, 1928. He sang it while playing his guitar and accompanied by banjoist Dock Boggs.[19] The record was released by Vocalion Records (Vo 5208) and sold well,[20] and he recorded it once more in 1931.[21] As the first released recording of the song, its melody and lyrics formed the footing for subsequent versions and variations.[5] Although a few singers had also recorded the song, it faded to relative obscurity until The Stanley Brothers recorded their version in 1950 and helped popularized the song in the 1960s.

The use of the song in the 2000 moving picture O Brother, Where Art Thou? led to its renewed popularity in the 21st century. The song has since been covered past many singers, from the Norwegian girl-group Katzenjammer to the winner of the eighth flavor of The Voice Sawyer Fredericks.[15] [22]

Stanley Brothers [edit]

| "I Am a Human of Constant Sorrow" | |

|---|---|

| Song by The Stanley Brothers | |

| Released | May 1951 (1951-05) |

| Recorded | November 3, 1950 (1950-11-03) |

| Genre |

|

| Length | two:56 |

| Label | Columbia |

| Songwriter(south) | Unknown |

| Official sound | |

| "I'g A Man Of Constant Sorrow" on YouTube | |

On November 3, 1950, The Stanley Brothers recorded their version of the vocal with Columbia Records at the Castle Studios in Nashville.[8] The Stanleys learned the song from their father Lee Stanley who had turned the song into a hymn sung a cappella in the Primitive Baptist tradition. The arrangement of the song in the recording however was their own and they performed the song in a faster tempo.[8] This recording, titled "I Am a Human being of Abiding Sorrow", was released in May 1951 together with "The Lonesome River" equally a single (Columbia 20816).[23] Neither Burnett nor Arthur copyrighted the vocal, which allowed Carter Stanley to copyright the song every bit his own work.[21]

On September 15, 1959, the Stanley Brothers re-recorded the vocal on Male monarch Records for their album Everybody's Country Favorite. Ralph Stanley sang the solo all the style through in the 1950 version, just in the 1959 version he was joined by other members of the band in added refrains. The fiddle and mandolin of the early version were also replaced by guitar, and a verse was omitted.[24] [25] This version (King 45-5269) was released together with "How Mountain Girls Can Love" as a single that October 1959.[26]

In July 1959, the Stanley Brothers performed the song at the Newport Folk Festival,[27] which brought the vocal to the attention of other folk singers. It led to a number of recordings of the song in the 1960s, most notably past Joan Baez (1960),[28] Bob Dylan (1961), Judy Collins (1961), and Peter, Paul and Mary (1962).[29]

Bob Dylan [edit]

| "I Am a Man of Constant Sorrow" | |

|---|---|

| Song by Bob Dylan | |

| Released | March 19, 1962 (1962-03-19) |

| Recorded | November 1961 (1961-eleven) |

| Genre |

|

| Length | three:10 |

| Label | Columbia |

| Songwriter(southward) | Unknown |

In November 1961 Bob Dylan recorded the song, which was included as a track on his 1962 eponymous debut album as "Man of Constant Sorrow".[13] [30] Dylan's version is a rewrite of the versions sung by Joan Baez, New Lost City Ramblers (Mike Seeger'due south band), and others in the early 1960s.[16] Dylan also performed the vocal during his starting time national US television receiver appearance, in the spring of 1963.[31] Dylan'south version of the song was used by other singers and bands of 1960s and 70s, such as Rod Stewart and Ginger Baker's Air Force.

Dylan performed a different version of the song that is a new accommodation of Stanleys' lyrics in his 1988 Never Catastrophe Tour.[xiii] He performed the song intermittently in the 1990s, and also performed it in his European bout in 2002.[xvi] A operation was released in 2005 on the Martin Scorsese PBS goggle box documentary on Dylan, No Direction Dwelling, and on the accompanying soundtrack album, The Bootleg Series Vol. seven: No Direction Domicile.[32] [33]

Ginger Baker'southward Air Force [edit]

| "Human of Constant Sorrow" | |

|---|---|

| Song by Ginger Baker'due south Air Strength | |

| from the album Ginger Baker's Air Forcefulness | |

| Released | March 1970 (1970-03) |

| Genre | Stone |

| Length | three:31 |

| Label | ATCO Records, Polydor |

| Songwriter(south) | Unknown |

The vocal was recorded in 1970 by Ginger Baker'southward Air Force and sung by Air Force guitarist and vocalist (and onetime Moody Blues, time to come Wings member) Denny Laine.[34] The single was studio recorded, merely a live version, recorded at the Royal Albert Hall, was included in their eponymous 1970 debut album. The band used a tune similar to Dylan's, and for the most office as well Dylan's lyrics (only substituting 'Birmingham' for 'Colorado'). The arrangement differed significantly, with violin, electric guitar, and saxophones, although information technology stayed mainly in the major scales of A, D and E. It was the ring's only nautical chart single.

Charts [edit]

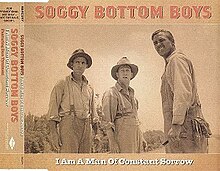

Soggy Bottom Boys [edit]

| "I Am a Homo of Constant Sorrow" | |

|---|---|

| |

| Vocal past The Soggy Lesser Boys | |

| from the anthology O Brother, Where Art K? | |

| Released | December 5, 2000 (2000-12-05) |

| Genre |

|

| Length | 4:20 |

| Label | Mercury Nashville |

| Songwriter(south) | Unknown |

| Producer(s) | T Bone Burnett |

| Official audio | |

| "I Am A Homo Of Abiding Sorrow" (With Band) on YouTube | |

A notable embrace, titled "I Am a Man of Constant Sorrow", was produced past the fictional folk/bluegrass group The Soggy Bottom Boys from the film O Blood brother, Where Art Thou?.[2] The producer T Bone Burnett had previously suggested the Stanley Brothers' recording as a song for The Dude in the Coen brothers' film The Large Lebowski, but it did not make the cut. For their next collaboration, O Brother, Where Art Thou?, he realized that the vocal would suit the main grapheme well.[two] [37] The initial plan was for the vocal to be sung by the movie'south lead thespian, George Clooney; however, information technology was found that his recording was not up to the required standard.[38] Burnett after said that he had only two or three weeks to piece of work with Clooney, which was not enough time to prepare Clooney for the recording of a credible striking country record.[37]

The song was recorded by Dan Tyminski (lead vocals) , with Harley Allen and Pat Enright, based on the Stanleys' version.[15] Tyminski as well wrote, played, and inverse the guitar role of the arrangement.[37] Two versions by Tyminski were found in the soundtrack album, with different backup instruments. In the film, it was a hitting for the Soggy Bottom Boys, and would afterwards become a existent hit off-screen. Tyminski has performed the vocal at the Crossroads Guitar Festival with Ron Block and live with Alison Krauss.

The song received a CMA Honor for "Single of the Year" in 2001 and a Grammy for "All-time State Collaboration with Vocals" in 2002. The vocal was also named Song of the Year by the International Bluegrass Music Clan in 2001.[39] Information technology peaked at No. 35 on Billboard'south Hot Country Songs nautical chart.[15] Information technology has sold over a million copies in the U.s. by November 2016.[forty]

Personnel [edit]

Source: [41]

- Banjo – Ron Block

- Bass – Barry Bales

- Dobro – Jerry Douglas

- Fiddle – Stuart Duncan

- Guitar – Chris Sharp

- Harmony vocals – Harley Allen, Pat Enright

- Lead vocals, guitar – Dan Tyminski

- Mandolin – Mike Compton

- Arranged by – Carter Stanley

Charts [edit]

Others [edit]

- 1920s – American Delta blues artist Delta Bullheaded Baton in his song "Hidden Man Blues" had the line 'Man of sorrow all my days / Left the home where I been raised.'[44]

- 1937 – Alan Lomax recorded Sarah Ogan Gunning's performance of her version, "I Am a Girl of Constant Sorrow", for the Library of Congress's Archive of American Folk Song. Her version was as well covered by other singers such as Peggy Seeger (her melody nonetheless is more than similar to Arthur'southward version), Tossi Aaron, and Barbara Dane. She recorded the song once more at the 1964 Newport Folk Festival, and as well released a recording in her album, Girl of Abiding Sorrow, in 1965.[xiv]

- 1947 – Lee and Juanita Moore's performance at a radio station WPAQ was recorded and afterwards released in 1999. They were granted a new copyright registration in 1939 for their treatment of the vocal.[2] [45]

- 1960 – A version of the song, "Girl of Abiding Sorrow", was recorded past Joan Baez in the summer of 1960.[28] This version was left off the original release of her debut anthology Joan Baez in 1960 on the Vanguard label, but was included as a bonus runway on the 2001 CD-reissue version of the album.[46] [47] Baez has also recorded "Man of Constant Sorrow" with no change in gender.[48]

- 1961 – Judy Collins's 1961 debut album, A Maid of Constant Sorrow, took its name from a variant of the song which was included on the anthology.[49]

- 1961 – Roscoe Holcomb recorded a version.[four]

- 1962 – It appears on Mike Seeger's album Former Time Country Music, Folkways FA 2325.[50] Mike Seeger recorded iii versions of the song.[4]

- 1962 – in their 1962 self-titled debut album, Peter, Paul and Mary recorded another version as "Sorrow".[51]

- 1966 – Information technology was recorded by Waylon Jennings on his 1966 major-characterization debut Folk-Country.[52]

- 1969 – Rod Stewart covered the vocal in his debut solo album. It was based on Dylan's version simply with his own arrangement.[53]

- 1972 – An a cappella version appears on The Dillards' 1972 LP Roots and Branches.[54] This version had only ii verses and replaced Kentucky with Missouri.

- 1993 – "Man of Abiding Sorrow" was i of many songs recorded by Jerry Garcia, David Grisman, and Tony Rice one weekend in February 1993. Jerry's taped copy of the session was later stolen by his pizza delivery man, somewhen became an underground classic, and finally edited and released in 2000 as The Pizza Tapes.[55]

- 2003 - Skeewiff "Man of Abiding Sorrow" was ranked 96 in the Triple J Hottest 100, 2003, released on Book 11 disk ane track 20.[56]

- 2012 - Charm Urban center Devils released "Human being Of Constant Sorrow" which charted on diverse Billboard rock charts - No. 25 on Mainstream Rock Songs[57] No. 22 on Agile Rock,[58] and No. 48 on Hot Stone Songs.[59]

- 2015 – Dwight Yoakam covered the vocal in his album Second Hand Center. Yoakam'south rendition has been described as having a 'rockabilly' sound.[60] [61]

- 2015 – Blitzen Trapper covered the song exclusively for the black comedy–crime drama television series Fargo, which played over the credits of the "Rhinoceros" episode of the second season.[62]

- 2018 – Home Gratis, covered the song in a country / a capella style. It was released also on their album Timeless.[63]

- 2021 - In the Aqueduct 4 sitcom We Are Lady Parts, the chief character, Amina, sings a variation of the vocal with the lyrics inverse to fit her situation.[64]

Parodies [edit]

In 2002, Cledus T. Judd recorded a parody titled "Man of Constant Borrow" with Diamond Rio on his anthology Cledus Envy.[65]

References [edit]

- ^ "'O Blood brother' Soundtrack Rules 44th Annual Grammy Awards". BMI. Feb 27, 2002.

- ^ a b c d eastward f g h Steve Sullivan (October 4, 2013). Encyclopedia of Great Popular Vocal Recordings, Volume ii. Scarecrow Press. pp. 254–255. ISBN978-0810882959.

- ^ "Homo of Constant Sorrow – Richard Burnett's Story", Old Time Music, No. 10 (Autumn 1973), p. 8.

- ^ a b c d e f m Todd Harvey (2001). The Formative Dylan: Transmission and Stylistic Influences 1961-1963. Scarecrow Press. pp. 65–67. ISBN978-0810841154.

- ^ a b c d east f yard John Garst (2002). Charles K. Wolfe; James E. Akenson (eds.). Country Music Almanac 2002. University Press of Kentucky. pp. 28–xxx. ISBN978-0-8131-0991-6.

- ^ "Isaiah 53:three". Bible Gateway.

- ^ George Pullen Jackson (1943). Down-E Spirituals and Others. pp. 70–71.

- ^ a b c d Steve Sullivan (Oct 4, 2013). Encyclopedia of Great Popular Song Recordings, Book 2. Scarecrow Press. pp. 296–297. ISBN978-0810882959.

- ^ John Garst (2002). Charles K. Wolfe; James Eastward. Akenson (eds.). Land Music Annual 2002. University Press of Kentucky. pp. 30–37. ISBN978-0-8131-0991-vi.

- ^ "Dr. Ralph Stanley: "Human of Abiding Sorrow: My Life and Times" autobiography due out Oct xv". www.bluegrassjournal.com. Archived from the original on Feb 19, 2012.

- ^ Stanley discusses vocal'due south origins on the Diane Rehm Show Archived 2009-x-16 at the Wayback Machine (link to sound programme'southward spider web page)

- ^ a b c d "Folk Telephone: "Man of Abiding Sorrow"". The Music Court. June 18, 2010.

- ^ a b c d east Paul Williams (December xv, 2009). Bob Dylan: Performance Artist 1986-1990 And Across (Mind Out Of Time) (Kindle ed.). Omnibus Press. ISBN978-0857121189.

- ^ a b c "Sarah Ogan Gunning - Girl of Constant Sorrow". Folk Legacy.

- ^ a b c d east f Evan Schlansky (June xxx, 2011). "Behind The Song: "Man Of Constant Sorrow"". American Songwriter.

- ^ a b c Oliver Trager (2004). Keys to the Rain: The Definitive Bob Dylan Encyclopedia. Billboard Books. pp. 411–412. ISBN978-0823079742.

- ^ Robert Shelton (4 April 2011). No Management Abode: The Life and Music of Bob Dylan. Omnibus Printing. ISBN978-1849389112.

- ^ Robert Shelton (four Apr 2011). No Direction Habitation: The Life and Music of Bob Dylan. Jitney Printing. ISBN978-1617130120.

- ^ Greil Marcus (2010). Bob Dylan by Greil Marcus: Writings 1968-2010 . PublicAffairs,U.Due south. p. 394. ISBN9781586489199.

- ^ Charles One thousand. Wolfe (November 26, 1996). Kentucky Country: Folk and Country Music of Kentucky (Reprint ed.). Academy Press of Kentucky. p. 36. ISBN978-0813108797.

- ^ a b David W. Johnson (24 January 2013). Lonesome Melodies: The Lives and Music of the Stanley Brothers. University Press of Mississippi. pp. 23–24. ISBN978-1617036460.

- ^ "Sawyer Fredericks Auditions For The Voice With "I Am A Man Of Abiding Sorrow"". The San Francisco Globe. March xx, 2015.

- ^ "Stanley Brothers, The & Clinch Mountain Boys, The* – The Lonesome River / I'm A Man Of Constant Sorrow". Discogs.

- ^ Gary B. Reid (December fifteen, 2014). The Music of the Stanley Brothers. University of Illinois Press. p. 103. ISBN978-0252080333.

- ^ David W. Johnson (24 January 2013). Lonesome Melodies: The Lives and Music of the Stanley Brothers. Academy Printing of Mississippi. p. 169. ISBN978-1617036460.

- ^ "Stanley Brothers". Bluegrass discography.

- ^ Gary B. Reid (December 15, 2014). The Music of the Stanley Brothers. Academy of Illinois Press. p. 100. ISBN978-0252080333.

- ^ a b Tom Moon (August 4, 2008). 1,000 Recordings to Hear Before Yous Die . Workman Publishing Company. p. 39. ISBN978-0761139638.

- ^ Richard Middleton (September 5, 2013). Voicing the Pop: On the Subjects of Popular Music (ebook ed.). ISBN9781136092824.

- ^ Jerry Hopkins (September 20, 1969). "'New' Bob Dylan Album Bootlegged in 50.A." RollingStone.

- ^ Michael Greyness (21 September 2006). The Bob Dylan Encyclopedia. Bloomsbury Academic. p. 76. ISBN978-0826469335.

- ^ John Nogowski (15 July 2008). Bob Dylan: A Descriptive, Critical Discography and Filmography, 1961-2007 (second Revised ed.). McFarland & Co Inc. ISBN978-0786435180.

- ^ Vince Farinaccio (2007). Goose egg to Plow Off: The Films and Video of Bob Dylan. p. 246. ISBN9780615183367.

- ^ "Ginger Baker'south Air Force". AllMusic.

- ^ "Ginger Baker'due south Air Force Chart History (Hot 100)". Billboard.

- ^ "Tiptop RPM Singles: Issue 3828." RPM. Library and Athenaeum Canada. Retrieved 30 January 2021.

- ^ a b c T Bone Bennett (Baronial 22, 2011). "O Blood brother, Where Art Thousand?". Huffington Mail.

- ^ Ben Child (Jan 29, 2014). "X things we learned from George Clooney's Reddit AMA". The Guardian.

- ^ "Recipient History". IBMA. Archived from the original on 2018-01-03. Retrieved 2015-06-04 .

- ^ Bjorke, Matt (November 28, 2016). "Tiptop thirty Digital Singles Sales Report: November 28, 2016". Roughstock.

- ^ O Brother, Where Art G? (2000), Mercury Records, 170 069-two

- ^ "Soggy Bottom Boys Feat. Dan Tyminski – I Am A Human being Of Constant Sorrow" (in French). Les classement unmarried.

- ^ "Soggy Bottom Boys Chart History (Hot Land Songs)". Billboard.

- ^ "Delta Blind Billy - Hidden man blues". Annal.org.

- ^ "WPAQ: Vocalization of the Bluish Ridge Mountains". AllMusic.

- ^ Joan Baez Allmusic link

- ^ James E. Perone (October 17, 2012). The Album: A Guide to Pop Music'southward Most Provocative, Influential, and Of import Creations. Praeger. ISBN978-0313379062.

- ^ "Joan Baez – Very Early on Joan". Discogs.

- ^ Trent Moorman (Feb 11, 2015). "Judy Collins Has Done Everything (Except Busking)". The Stranger.

- ^ Neb C. Malone (24 October 2011). Music from the True Vine: Mike Seeger's Life and Musical Journeying. The University of North Carolina Press. p. 119. ISBN978-0807835104.

- ^ Craig Rosen (30 September 1996). The Billboard book of number one albums: the inside story behind pop music's blockbuster records. Billboard Books.

- ^ Vladimir Bogdanov; Chris Woodstra; Stephen Thomas Erlewine (Nov 1, 2003). All Music Guide to Country: The Definitive Guide to Land Music. Backbeat Books. p. 376. ISBN978-0879307608.

- ^ Eric v.d. Luft (October 9, 2009). Die at the Right Time!: A Subjective Cultural History of the American Sixties. Gegensatz Press. ISBN9781933237398.

- ^ John Einarson (2001). Desperados: The Roots of Country Rock . Cooper Foursquare Press. p. 206. ISBN978-0815410652.

- ^ Vladimir Bogdanov; Chris Woodstra; Stephen Thomas Erlewine (nineteen December 2003). All Music Guide to Country: The Definitive Guide to State Music (2nd Revised ed.). Backbeat Books. ISBN978-0879307608.

- ^ "Hottest 100 - History - 2003". www.abc.net.au.

- ^ "Mainstream Rock songs: Baronial four, 2012". Billboard.

- ^ "Active Rock: June 30, 2012". Billboard.

- ^ "Hot Rock Songs: June 9, 2012". Billboard.

- ^ "Review: Dwight Yoakam, '2nd Hand Centre'". NPR.org.

- ^ Sterling Whitaker (Feb 5, 2015). "Dwight Yoakam Announces Details of 15th Studio Anthology". Taste of Land.

- ^ "Review: 'Fargo' - 'Rhino': Attack on precinct Luverne?". HitFix. November 17, 2015.

- ^ "Dwelling house Free'southward Roots Run Deep In "Man of Constant Sorrow" Video". The State Note. 29 September 2018. Retrieved 6 April 2019.

- ^ "We Are Lady Parts". Aqueduct 4 . Retrieved 2021-05-24 .

- ^ Cledus Green-eyed (CD liner notes). Cledus T. Judd. Nashville, Tennessee: Monument Records. 2008. 85897.

{{cite AV media notes}}: CS1 maint: others in cite AV media (notes) (link)

Further reading [edit]

- John Garst (2002). ""Homo of Abiding Sorrow": Antecedents and Tradition". In Charles Chiliad. Wolfe; James Due east. Akenson (eds.). Country Music Almanac 2002. University Printing of Kentucky. pp. 26–53. ISBN978-0-8131-0991-6.

External links [edit]

- "Folk Telephone: "Man of Abiding Sorrow"". The Music Court. June eighteen, 2010. Contains lyrics for Burnett's and the 1950 Stanley Brothers' versions

- "Man of Constant Sorrow". Bob Dylan'south Musical Roots. Lyrics for Bob Dylan'southward 1961 recording and Stanley Brothers' 1959 version from Newport Folk Festival

krameryeakedealke.blogspot.com

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Man_of_Constant_Sorrow

0 Response to "Man of Constant Sorrow O Brother Where Art Thou"

Post a Comment